Which elementary school on the island of Hawai‘i has the most intensive program in Japanese language? Would you believe it is a Hawaiian language medium school, specifically, Ke Kula ‘O Nāwahīokalani‘ōpu‘u — Nāwahī, for short — located in Kea‘au in the Puna District? And, would you believe that it is a school in which over 95 percent of the students are of Hawaiian ancestry?

Nāwahī Japanese language program is part of the school’s “heritage language program” to honor non-Hawaiian ancestors. Japanese language has been taught at Nāwahī since 1994 and is the strongest part of that program. The current Japanese teacher, “Pilialoha” Kimiko Tomita Smith, has three Hawaiian language degrees: a B.A., teaching certificate and an M.A. And, she teaches Japanese to her students speaking Hawaiian.

Nāwahī School grew out of the Hawaiian language revitalization effort that began in the early 1980s. It is the main laboratory school site of the Hawaiian language college at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo and includes a preschool through grade 12 program that is taught, operated and administered totally in Hawaiian. There are 360 students on its main campus in Kea‘au, with satellite campuses in Waimea on Hawai‘i island and in Wai‘anae on O‘ahu.

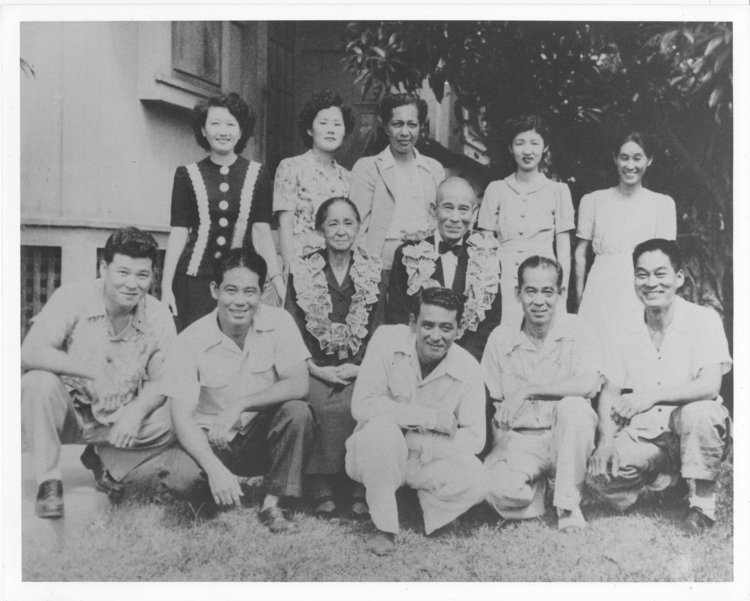

The Harman keiki have been taught their Japanese mo‘okü‘auhau (genealogy) in Hawai‘i. Their great-great-grandparents, Noburo (kneeling, third from left) and Mariah (Lono) Suganuma (standing, third from left), are pictured in this photo with Noburo’s parents, Seiji and Nao Suganuma (wearing lei). (Photo courtesy Harman family)

The mission of Nāwahī is to restore Hawaiian as a living language of families and communities. In 1986, the state Legislature removed a ban that had been placed on Hawaiian medium education in 1896. Ninety years of English medium education had totally broken transmission of Hawaiian from grandparents and parents to children on Hawai‘i island.

That break is beginning to mend.

Today at Nāwahī, approximately 33 percent of the children enrolled have spoken Hawaiian from birth. Their parents either learned Hawaiian at Nāwahī itself or at a university program. Still other parents began to learn and use Hawaiian with their children after the children began school at Nāwahī.

But Hawaiian isn’t the only language spoken by Nāwahī students.

At Nāwahī Kea‘au campus, oral and written Japanese is studied by all students in grades one through six. At grade five, English is introduced as a world language, continuing on through grade 12. English classes are the same length as Japanese classes and, like the Japanese classes, are taught through Hawaiian and from the perspective of the Hawaiian language.

By the end of grade 10, students have had more Japanese language instruction than English. By high school graduation, however, Nāwahī students have enough proficiency in English to function in English medium universities. Like foreign students who enroll in American universities, Nāwahī students have the cognitive advantage of high bilingualism, and, also like them, Nāwahī students must devote some extra time in college to learning English equivalents for academic terms from the non-English language they used in high school. That bit of extra work is accepted as part of revitalizing Hawaiian. This shared non-English high school background, plus a background in Chinese characters, provides a unique connection with East Asian foreign students in college.

Since its first graduating class in 1999, Nāwahī has had a 100 percent high school graduation rate, with over 80 percent of its students enrolling directly into college. Most enroll in the University of Hawai‘i system. Among other universities from which Nāwahī students have graduated are Seattle University, Portland State, Loyola Marymount, Northern Arizona and Stanford. Nāwahī high school graduation and college enrollment rates are considerably higher than the state’s average.

My own association with Nāwahī is as a university linguist affiliated with it and researching its programming. I am also the parent of graduates from Nāwahī. One of my areas of interest is the conflict between English medium testing requirements under the federal No Child Left Behind law and best practice for education through Hawaiian.

The majority of parents at Nāwahī have boycotted NCLB testing. Partnering with American Indian schools, Nāwahī is seeking a solution from the U.S. Department of Education parallel to that given to Puerto Rico, where public education is through Spanish. Of assistance in this effort are a number of federal laws relating to indigenous peoples. There are also U.S. Supreme Court decisions supportive of language minorities, including one from Hawai‘i regarding Japanese language schools (Farrington vs. Tokushige).

The Harman family is one of the Nāwahī families in which only Hawaiian is spoken in the home. I interviewed the three Harman children last month regarding their Japanese language studies. The oldest daughter, Kalämanamana, is in grade eight. Her sister Pine is in the third grade, and Leha, their brother, is in the fourth grade. Our interview was conducted in Hawaiian. I have translated and summarized their responses.

Wilson: “How long have you been studying Japanese?”

Leha: “I have had four years.”

Pine: “Three years.”

Kalāmanamana: “I had four years. My courses ended at grade five and Japanese started in second grade for us.”

Wilson: “What do you and other students think about studying Japanese at Nāwahī?”

Leha: “We really like it. The Japanese students, like ourselves, want to know our language. Most of the students in my class are Japanese and feel we need to learn it. But, even the children who are not Japanese like learning Japanese.”

Kamaehu Glendon, a fourth-grader, reviews kanji.

I knew that the Harman children were part-Japanese, but I did not realize that in some Nāwahī classes, a majority of students had Japanese ancestry. Nāwahī integrates the Hawaiian cultural focus on ancestors into its curriculum, including the study of genealogies. Students have a good idea of their various ancestries, even in the lower grades. The Harman children told me that besides Hawaiian and Japanese, they are German, Filipino, Welsh, Korean, Irish and Scottish.

In answer to my questions regarding what they liked about studying Japanese, the Harman children chimed in about songs, games and also about learning to read the language. They described an annual school Japanese Day held with special visitors and hands-on cultural presentations that included taiko, origami, kimono dressing and calligraphy.

I then asked them about Japanese culture outside of school.

Kalāmanamana said that their mother takes them to bon dances, that they eat Japanese foods and that they sometimes watch Japanese cartoons. Leha mentioned that he had a Boy’s Day carp in his room.

The Harman children said they had opportunities to speak Japanese with visitors to the school from Japan. There were two types of such visitors — those interested in language revitalization who came during regular school time, and others who visited the afterschool hula group taught by their mother and father. The Harman children said they had the most contact with the visitors interested in hula, some of whom only spoke Japanese. They also said that their aunt had traveled to Japan for hula and that they had met other Japanese speakers through her.

And, they said, “She gave us a kendama (wood and string toy) from Japan that is different from those that the other children have at Nāwahī. It has a longer string!”

Leha said that some of the Japanese visitors could speak English and that he used English with those Japanese speakers when he could not express enough in Japanese. I asked him how he had learned to speak English. As a fourth-grader, he had not yet studied English in a classroom setting.

“I learned it from talking to my cousins,” he said.

“What about reading English?” I asked.

“Can you read English, too?”

“Some,” he replied.

I did not test Leha on his English reading ability. However, we videotaped his older sister just before she entered the fifth grade. The tape shows Kalāmanamana reading a random page in the book, “The Chronicles of Narnia.” In the tape, she says that she could already read Hawaiian, so she just started reading English on her own without any adult help.

The way in which Nāwahī students teach themselves to read English once they are proficient Hawaiian readers is what linguists call “literacy transfer.” Literacy transfer is easiest between languages that share the same or similar features of their writing systems, such as the way Hawaiian and English share the Roman alphabet.

The Japanese language program at Nāwahī uses another form of literacy transfer in teaching children to read Japanese. It has its source in the Hawaiian reading program at Nāwahī, which teaches initial literacy through a syllable chart. That Hawaiian syllable chart has direct parallels with the hiragana (alphabet) chart used to teach initial reading in Japan. Because of the similarity in syllables, Nāwahī students can learn to read Hawaiian represented by hiragana and kanji characters. Once students are reading and writing Hawaiian with this system, reading actual Japanese is relatively simple.

Pilialoha-Sensei contrasts the difference between teaching students at Nāwahī how to read Japanese with teaching it to other students.

“Learning Japanese is very challenging for any learner,” she said. “Learning Chinese characters (kanji) is the hardest aspect of the Japanese language. I used to teach Japanese at UH-Hilo. At that time, many non-Asian university students frequently mentioned about this difficulty. For Nāwahī students, it is a totally different story. Since they are already bilingual in Hawaiian and English, learning an additional language and writing system is not difficult for them. They always tell me that learning Chinese characters is very easy.

“My experience is that these Hawaiian children are visual learners. They can visualize a Chinese character as a picture and retain that image very well. This is very amazing for a native speaker of Japanese, like me, because as a child, I had to write the same character hundreds and hundreds of times before memorizing it. It was not fun at all. Nāwahī students love writing Chinese characters.

“Another advantage that Nāwahī students have in learning Japanese is the similarity in pronunciation between Japanese and Hawaiian. My students speak Japanese without any strong accent. After practicing a new Japanese song a few times, they soon start singing it with ease, like Japanese kids.”

I do not know of any elementary school on Hawai‘i island that teaches oral and written Japanese as regular graded academic content. On O‘ahu, however, there are a number of schools that have implemented the “International Baccalaureate Program” for various languages, including Japanese.

The International Baccalaureate guidelines call for approximately 12 hours per year of second language study at grade two and below, 18 hours between grades three and five, and 50 hours at grade six and above. Nāwahī requires 70 hours (35 hours in oral Japanese and 35 hours practice in the writing system) at all elementary-level grades.

“Pilialoha” Kimiko Tomita Smith-Sensei with her Nāwahī students.

Not many people in Hawai‘i know about Nāwahī teaching of Japanese through Hawaiian. Neither do they know about modern Hawaiian language medium education. Ironically, however, Hawaiian medium education is fairly well known in Japan.

A unit on Hawaiian medium education is included in the Japan government-approved middle school English curriculum. Millions of students in Japan read this selection annually.

A Japanese perspective, however, is very evident in how both Hawaiian and English are viewed within the unit. For example, the reading includes a reference to Hawaiian being a “very musical language” with “only 45 syllables,” compared to the 46 basic Japanese hiragana symbols, rather than the Roman letters of English.

The unit closes with the following thoughts for Japanese students to consider: “Imagine that English has taken the place of the Japanese language here in Japan. What happens to your culture and identity?

. . . In this class we are going to study English of course, but I want you to remember that your mother tongue is the most important language in the world.”

For Nāwahī students, the Hawaiian language is the most important language in the world. But, the question of identity is often more complex than in Japan. At the end of my interview with the Harman children, I asked them if there was anything else that they wanted to add. They started whispering among themselves. I heard the word “mo‘okū‘auhau.” Then Kalāmanamana said to me.

“You forgot to ask us our mo‘okū‘auhau (genealogy). The name is Noburo Suganuma. He was the first Japanese in our mo‘okū‘auhau. He is our great, great-grandfather.”

For Nāwahī Hawaiian language medium school, identity involves honoring all of one’s ancestors in a Hawaiian way — through genealogy — and through building connections to ancestral homelands through a special talent for language learning.

Dr. William H. “Pila” Wilson was born in Honolulu to parents who settled in Hawai‘i during World War II. He teaches at Ka Haka ‘Ula o Ke‘elikōlani College of Hawaiian Language at the University of Hawai‘i – Hilo, where he specializes in Hawaiian grammar, the history of the Hawaiian language and language revitalization. Wilson has also played a key role in developing state laws for education through Hawaiian and in establishing federal policies to protect and promote native American languages. He and his wife, Dr. Kauanoe Kamanā, were among the founding members of ‘Aha Pūnana Leo, the Hawaiian language immersion preschool program. Their two children were educated at Nāwahī and their son was in the first graduating class of Nāwahī in 1999.