“ha ka, la ma, na pa, wa ʻa…” chant the children at the Pūnana Leo preschool as one of the older students leads them pointing out consonant vowel pairs on a wall chart (see Fig. 8.1). This is the “Hakalama” syllabary used in these Hawaiian language medium preschools to teach early literacy. Later in the day some of the older Pūnana Leo students will be reading novel Hawaiian words and sentences using the Hakalama.

These 3- and 4-year-old children are reaping a unique benefit of attending pre-school through the endangered Native Hawaiian language. They begin to master reading Hawaiian approximately 2 years before their peers in English medium education begin to master reading English. Features of their Hawaiian language of instruction and its writing system align closely with ordered stages of childhood brain development allowing for early literacy acquisition. The Polynesian Hawaiian language is especially well-suited for learning to read by syllables, a method unavailable for English.

Fig. 8.1 Pūnana Leo student reciting the Hakalama syllabary

By the time the brains of Pūnana Leo graduates are ready to learn to read by phonemes – the single sound method required for reading English – these children will be in elementary school and will have already developed reading skills in Hawaiian. Later, these children will transfer skills in reading Hawaiian to reading Japanese and English. This chapter will explore the science behind the Hakalama, some of its history and some of the challenges that those using it face in the context of contemporary American education.

The Relationship of Metalinguistic Development to Early Literacy

To learn to read, a speaker of a language must be able to consciously analyse that language into segments and connect those segments to written symbols. The growth of a child’s brain through stages where such language analysis occurs is the child’s metalinguistic development. Over the past several decades, research has provided much information about how that progression relates to the acquisition of literacy. At an early stage of development, children begin to separate out full words from streams of speech. The next stage involves the ability to separate out the syllables of a word. The last skill is to separate phonemes from a syllable (Fox & Routh, 1974; Lonigan, 2006; Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2000). Figure 8.2 illustrates these stages with the English word “crocodile” and the Hawaiian word “hīnālea”, ‘Thalassoma duperrey’, a type of fish.

Fig. 8.2 Metalinguistic awareness stages and ages

The ages chosen to illustrate the stages in Fig. 8.2 are not absolute, but represent approximations (Fowler, 1991; Lonigan, Burgess, Anthony, & Barker, 1998) and relative difficulty of conscious analysis (Burgess, 2006; Carroll, Snowling, Hulme, & Stevenson, 2003; Lonigan, 2006). Full mastery of one level is not required before children move on to aspects of the next level. Furthermore, the above metalinguistic ordering can be further broken down into substeps. For example, between the syllable and the phoneme, is a substep where a syllable is broken into two parts: a beginning or “onset” and an ending or “rime”. In this example, the initial syllable “croc-” of “crocodile” begins with the onset “cr-“and ends with the rime “-oc”.

The individual steps in childhood metalinguistic development differ in importance for acquiring literacy in different languages. In Chinese, the focus of initial literacy is primarily on symbols representing single-morpheme, single-syllable words. Because of this focus, initial meaningful acquisition of reading through Chinese characters can begin quite young – around age three, as is common in Hong Kong (Zhang & McBride-Chang, 2011). For Japanese, initial acquisition of reading is focused on syllables, or more properly “mora” – essentially short syllables – that form multi-syllable words. Childhood literacy acquisition in Japanese typically begins with the hiragana syllabary around age four (Matsumoto, 2004; Sakamoto, 1975). For English, the focus is primarily on phonemes, which are represented with letters of the English version of the Roman alphabet. Enrolment in first grade at age six, is generally when children are expected to seriously begin mastery of English reading (Armbruster, Lehr, & Osborn, 2003; Mather & Wendling, 2012; National Reading Panel, 2000).

Late initial mastery of reading in English compared to that in Chinese and Japanese can be related to the relative difficulty of metalinguistic recognition of phonemes. While syllabic awareness appears naturally in children, phonemic awareness is less natural and may not develop, even in adults, without instruction in an alphabetic writing system (Fowler, 1991; Adrian, Alegria, & Morais, 1995; Nagy & Anderson, 1995; Carroll et al., 2003, Share, 2014).

Hawaiian has a number of advantages in its structure and writing system that make it easier to learn to read than English. Hawaiian words are generally multisyllabic and constructed from 45 basic syllables that have both long and short versions. The syllabic structure of Hawaiian therefore makes it possible to memorize symbols for all Hawaiian syllables and begin reading syllabically before kindergarten. English words, on the other hand, are structured using over 15,000 different syllables making an English syllabary impractical (Baker, 2014).

Moving from syllabic reading to phonemic reading is also quite easy in Hawaiian. What are called huahakalama (“Hakalama unit symbols”) e.g., “ha”, “he”, “hi”, etc. are already separated into consonantal onset and vocalic rime phoneme units represented by distinct letters. Furthermore, the phonotactics of Hawaiian, that is the way that its phonemes are arranged in words, does not include the complicated consonant clusters at the beginning and ends of syllables that are a challenge in acquiring initial phonemic reading through English. For example, the single-syllable English word strips contains three initial consonants and two final consonants.

An additional advantage of Hawaiian is its highly regular writing system. Hawaiian is written with highly transparent phoneme to letter correspondences, parallel to Finnish, the European language with the most regular orthography. In contrast to Hawaiian and Finnish, English has a highly irregular orthography (Share, 2014). The irregularity of the English orthography plays a major role in it being the most difficult of the European languages in which to learn initial literacy. By the end of first grade, children in Finland can read Finnish with a rate of just 2% mistakes. This contrasts with a rate of 66% mistakes for first grade readers in England (Ziegler & Goswami, 2006).

The close alignment of the phonotactics of Hawaiian and its writing system played a major role in the high literacy outcomes of nineteenth century Hawaiian medium public education and its policy of initial childhood enrollment at age four (Pukui, Haertig, & Lee, 1972b). Subsequent to public Hawaiian medium education being outlawed in 1896, the Hawaiian language was nearly exterminated and Native Hawaiians, once the most literate of the major ethnic groups in Hawaiʻi, became the least literate in the islands (Wilson & Kamanā, 2006). The successes and challenges of contemporary early childhood literacy development in Hawaiian relate very much to a movement to overcome the effects of past and present political and societal barriers to use of Hawaiian (Wilson, 2012; Wilson & Kamanā, 2001).

The Pūnana Leo Hawaiian Preschools and Follow-Up Programing

Contemporary Hakalama syllabic reading and the term “Hakalama” itself developed in the Pūnana Leo preschools. The Pūnana Leo are full day, 5-day a week, 11-months per year private preschools conducted entirely through the Hawaiian language. They are operated at thirteen sites on various Hawaiian islands by the non-profit ʻAha Pūnana Leo. Students enroll at age three and remain in the program for 2 years.

Inspired by the Kōhanga Reo Māori language movement of New Zealand, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo was founded in 1983 to revitalize the highly endangered Hawaiian language. Similar movements are occurring worldwide (Grenoble & Whaley, 2006). At the founding of the ʻAha Pūnana Leo, the Hawaiian language was spoken fluently primarily by elders born before 1920 and by a small relic population of some 200 people of all ages on the remote island of Niʻihau (Wilson & Kamanā, 2001).

The ʻAha Pūnana Leo began a movement that has resulted in an integrated preschool through university (P-20) system of education through the medium of Hawaiian. That P-20 system is most fully developed and internally articulated in Hilo, Hawaiʻi. Hilo is the site of the ʻAha Pūnana Leo state administrative office, the Nāwahīokalaniʻōpuʻu (Nāwahī) laboratory school and the state Hawaiian language college Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani. Within this integrated total Hawaiian language-administered system, it is possible to enter at preschool, complete high school through Hawaiian, and then pursue a B.A., teaching certificate, master’s degree, and Ph.D. all through Hawaiian. Increasingly, the products of this system are raising their children as first language speakers of Hawaiian further strengthening the movement (Wilson, 2014).

We, ourselves, have been highly involved in the above three entities, being among their founders. We continue to teach in their various programs including Pūnana Leo and Nāwahī. Second language speakers of Hawaiian ourselves, we were among the first such couples raising children as first language speakers (Wilson & Kamanā, 2013). Both our children attended the Pūnana Leo O Hilo and graduated from Nāwahī. The establishment of the ʻAha Pūnana Leo’s Hakalama reading program, its further development, and in-service support to teachers on its use has in large part been the result of our work over the past 30 years.

The Establishment of the Hakalama

In early 1985, after closing an unsuccessful initial Pūnana Leo, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo opened two new sites with close supervision by Kamanā. The key factors in the success of these two subsequent sites was full use of Hawaiian by staff at all times and insistence that children respond in Hawaiian. The focus of these sites was on reproducing as much as possible the experiences of growing up in a Hawaiian-speaking home of the early twentieth century. Hawaiian culture includes attention to strict training of children from an early age and a focus on memorization. While originally lacking writing, Hawaiian culture is highly oriented toward symbolism. Hawaiians adopted the written word very quickly and integrated literacy into existing traditions (Pukui, Haertig, & Lee, 1972a, 1972b). The integration of literacy into Hawaiian culture can be seen until today in Niʻihau church services where the entire congregation rises individually regardless of age to read orally from the Bible.

Very young children do this initially with assistance from an adult (Williams, 2014). Similar traditions are also characteristic of a number of other Polynesian peoples (Tagoilelagi-Leota, McNaughton, MacDonald, & Ferry, 2005). Indigenous literacy traditions are also found elsewhere in the world, some of which involve syllabaries, for example, the Cherokee and Cree syllabaries (Share, 2014).

One elder working with Hawaiian language revitalizationists, Mrs. Mālia Craver, described how she was taught as a young child by her grandparents to recite the Hawaiian consonant-initial syllables in a simple chant as part of being taught to read Hawaiian at home (Craver, 1981). We wanted to reintroduce this custom into the Pūnana Leo. However, we also wanted the recitation of syllables to reflect changes to the Hawaiian orthography. These changes are important for maintaining in writing the distinctive pronunciation of the oral language not indicated in the Hawaiian alphabet standardized by missionaries from New England in 1826 (Schütz, 1994).

Mrs. Craver pronounced each consonant-vowel syllable with a long vowel. In order to reflect current spelling, we added a macron to indicate the long vowel sound. Then, we added in line-final position an additional consonant: the ʻokina or glottal stop indicated by a single open quote mark. This then left the short vowels, which we added in lines immediately above the original long vowel lines. Figure 8.3 illustrates the Pūnana Leo Hakalama chart with the even numbered lines 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10, except for the glottal stop-initial huahakalama, being the part originally demonstrated by Mrs. Craver.

Fig. 8.3 The ʻAha Pūnana Leo Hakalama chart

The Craver version and the 1985 Pūnana Leo version were nearly identical in pronunciation and rhythm at the long vowel level, however, our adding the short vowels required a different approach as it is impossible in Hawaiian to stress a “word unit” containing a single mora, i.e., a single short vowel. The solution was to pronounce short syllables in pairs as if they were two mora words, e.g., haka, lama, napa, waʻa. Through reciting the chart in this way, a contemporary name developed for it based on the first line, i.e., Hakalama.

We produced a Hakalama chart for the Pūnana Leo O Hilo and children recited it in a learning circle with each huahakalama pointed to as it was recited. We then experimented with teaching older children to read using cards with huahakalama written on them and fitting the words together with those cards. For example, “maka” ‘eye’ would be put together with a card with “ma” and a card with “ka”. From Hilo we expanded this practice to the other Pūnana Leo sites.

In 1986, after 3 years of lobbying state legislators, we convinced them to pass two pieces of landmark legislation. One provided an exemption to our Pūnana Leo teachers from preschool teacher training requirements. We needed this because we taught through a highly endangered language for which native speaker college-trained teachers and language-specific preschool teacher education did not exist. The other legislation removed a 90-year old ban on the use of Hawaiian in the public schools (Wilson & Kamanā, 2001).

When the state Department of Education did not open a Hawaiian language kindergarten for the 1986–1987 school year, we established a kindergarten at the Pūnana Leo O Hilo. That kindergarten was called Papa Kaiapuni Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian Environment Class). Use of the Hakalama in teaching reading was a key part of that Papa Kaiapuni Hawaiʻi. The next school year, the state allowed the Papa Kaiapuni Hawaiʻi into the public schools. The Hakalama followed the program into the public schools. There then followed 12 years of intense attention to moving up one grade per year with new Hawaiian speaking teachers and new Hawaiian language materials required each year, all produced outside the state Department of Education. Indeed, when we began in the public schools in the 1987–1988 school year, teachers were expressedly told that there would be no literacy instruction through Hawaiian in the public school classrooms “because Hawaiian is an oral language” (personal communication Alohalani Housman, 2014.) The enrolled families and teachers simply refused that directive. The children had already learned basic reading of simple Hawaiian words under the ʻAha Pūnana Leo before they entered the state school site. Refusing to comply with that directive was the first of many acts of resistence that played a key role in the establishment of a full public stream of Hawaiian language medium education.

Adding the Vowel Lines

Once the first seniors had graduated from the Hawaiian language medium system in 1999, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo returned to focus on the preschool level and developing Hakalama curriculum materials for its schools. The Hakalama remained a purely consonant-initial chart until 2005 when the two vowel lines were added as shown in lines 11 and 12 in Fig. 8.3. Adding the vowel lines made it possible to spell all indigenous Hawaiian words from the chart.

A challenge in adding the vowel lines involves reciting them without glottal stops. The phonotactics of Hawaiian allow for the insertion of a meaningless glottal stop at the beginning of a phrase. To avoid those meaningless glottal stops, the recitation of the two final lines of the Hakalama chart is done as if those lines were part of a single long phrase beginning with the meaningful glottal stop at the end of line 10. That long phrase is internally integrated through insertion of non-phonemic “w” and “y” glides in a phenomenon somewhat like liaison in French. Such inserted glides are a characteristic of phrase internal speech in Hawaiian and must be practiced for fluent reading of the language.

Another Hakalama pronunciation issue involves the short vowels of line 11. Certain sequences of short vowels in Hawaiian coalesce in rapid speech to form diphthongs. Those diphthongs then affect stress placement and syllabication. To further the importance of attention to stress and timing, we established a method of clapping out the Hakalama. One clap is given for every short vowel and two claps for every long vowel or diphthong – that is one clap for each mora. The most challenging aspect of teaching initial Hawaiian literacy remains consonant-less vowels.

The ʻAha Nuʻukia and Hakalama Teacher Training

In 2005, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo began an annual summer week-long in-service teacher training retreat – the ʻAha Nuʻukia. The initial years of the ʻAha Nuʻukia focused on strengthening the Hawaiian language and cultural base of the schools as found in its Kumu Honua Mauli Ola philosophy (ʻAha Pūnana Leo and Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani, 2009). In the 2011 retreat we increased attention to the Hakalama. Since then, Hakalama teaching methodology has increased in sophistication and teachers have annually grown in their skills in teaching preschool Hawaiian reading and writing.

Once an individual child can chant the Hakalama and point out each symbol as it is pronounced, the next step is for the child to realize that the huahakalama symbols of the Hakalama can be used to represent any word or sentence in Hawaiian. At a very simple level, several of the long vowel huahakalama are themselves names of individual objects, e.g., hā ‘taro leaf stalk,’ kā ‘sweet potato runners,’ pā ‘plate.’ The next level of understanding is that those symbols also represent a word’s homonyms, for example, children are able to move from pā ‘plate’ to pā ‘shining of the sun.’ Children then move to building words that are reduplications, such as, pāpā ‘daddy’ and then other words from other phonotactic categories and finally full sentences and paragraphs. The ʻAha Nuʻukia is crucial as the ʻAha Pūnana Leo faces major workforce challenges. Teachers are typically hired with minimal understanding of the use of Hawaiian as a medium of education. Once trained and supported with university classes, many teachers leave the ʻAha Pūnana Leo for better paying employment in the public elementary school Hawaiian immersion program. That turnover averaged 18.5 % over 2012 and 2013 (Kēhaulani Shintani, personal communication, 2014). High turnover affects the ability to deliver a strong Hakalama reading program and requires constant attention to development of teacher skills to produce improved student outcomes (Fig. 8.4).

Fig. 8.4 Pūnana Leo teachers at the ʻAha Nuʻukia training

Assessing Early Literacy from a Hakalama Base

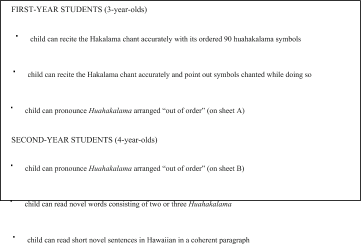

In 2011, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo developed assessments of student Hakalama mastery and began to test them out at the Pūnana Leo O Hilo. The assessments in their current stage of development address five skill areas. The assessments are given individually to children by a single test administrator and are timed at a length of 1 min each. Each assessment is given once at the beginning, middle, and end of the school year with 3- and 4-year-olds taking different assessments. The tested skills are illustrated in Fig. 8.5.

Fig. 8.5 Hakalama skill assessments

The test administrator has indicated that some children have been shy in demonstrating their skills to her, a stranger. Nevertheless, assessments indicate growth over the three test points and between the two age levels. At the end of the 2012– 2013 school year, 100 % of the 21 first-year students demonstrated an ability to individually chant portions of the 90 Hakalama chart (Test I); 70 % accurately pointed out some huahakalama while doing so (Test II); and 52 % identified one or more huahakalama arranged out of order (Test III). Among the 19 second-year students, 94.7 % (all but one) completed the year demonstrating the ability to identify one or more huahakalama out of order (Test III); 68 % decoded one or more novel words (Test IV); and 63 % accurately decoded words in a novel 114 word paragraph (Test V). Among the twelve students that read through part of the paragraph of Test V in the alloted time, the lowest word score was 5 words (red) and the highest was 30 words (blue), with the average being 17.5 words (green) (Fig. 8.6).

Fig. 8.6 The first 32 words (and translation) of the paragraph of test V

The ʻAha Pūnana Leo has been encouraged by continued growth in the skills of student cohorts. This indicates its teacher training is producing positive results. Critical pieces that have yet to be addressed include Hakalama reinforcement in the home and strategies for assisting students with distinctive difficulties. The goal is to have all Pūnana Leo students able to read a short novel paragraph before kindergarten entry.

Learning the Alphabet After Mastering Syllabic Decoding

Use of the Hakalama allows for early mastery of the alphabetic principle, i.e., systematic use of written symbols to represent the sounds of a language. Best practice for English medium preschools and kindergartens is to support the development of the alphabetic principle through first teaching the names of letters of the English alphabet followed by associating individual letters with English phonemes (Lonigan et al., 2000). Within the Hakalama methodology, naming letters follows rather than precedes – reading and writing by huahakalama. While Pūnana Leo schools teach traditional Hawaiian songs and dances using the alphabet, this cultural use differs from identification of individual letters as a base for beginning literacy.

The Hawaiian alphabet, illustrated in Fig. 8.7, differs from the English alphabet in the names of letters and in their ordering. The letters in set 2 of Fig. 8.7 are distinctive in representing non-indigenous phonemes found in the last names of some students, e.g., Silva, Fujimoto, Chang. There is also a limited number of Hawaiian words that use these borrowed letters, e.g., nāhesa ‘snake’, berita ‘covenant’, zebera ‘zebra’. Such words are taught through a phonological approach in early elementary school after children can already read. Other than for teaching the reading of that small number of borrowed words, the purposes of learning the alphabet within the Hakalama methodology are to allow oral spelling and to have a memorized order of letters for alphabetizing lists.

Fig. 8.7 Hawaiian alphabet (with names of letters)

Because most letter names in Hawaiian also name huahakalama, teaching the identification of letters by name before students can read and write using huahakalama can result in confusion in decoding and writing, for example, misspelling He nūnū kēlā. “That is a pigeon.” as hnnkl. As shown below, letter and huahakalama names can be differentiated grammatically, but the subtle difference in usage does not justify simultaneous learning of both the names of letters and huahakalama.

ʻO ka nū kēia. This is “nū” (the letter “n”.)

ʻO nū kēia. This is “nū” (the huahakalama “nū” or the word “nū” ‘roar of wind’.)¹

The Relationship of the Hakalama to Historical Practices

Mrs. Craver’s chant that inspired the development of the Hakalama was not restricted to her family, but was once a general practice among Hawaiians (Pukui et al., 1972b). It derived from Hawaiian traditions combined with the teaching methodology used by American Christian missionaries. There are, however, considerable differences between the Hakalama of the ʻAha Pūnana Leo and the missionary-produced school materials. Compare, for example, the chart in Fig. 8.8 and the Hakalama chart in Fig. 8.3.

Fig. 8.8 A nineteenth century Hawaiian literacy chart

The early missionary primer charts for Hawaiian began with a vertical list of the letters of the alphabet. This was then followed by vertical lists of two letter combinations starting with vowel combinations and then consonant plus vowel combinations. Next were vertical lists of a samplings of words consisting of increasing numbers of letters. Essentially the same method was used for teaching English literacy in eighteenth and nineteenth century New England (van Kleeck & Schuele, 2010). That method brought to Hawaiʻi by the missionaries also involved first spelling a word using letter names and then pronouncing that word. For example, the word “PA” was decoded in Hawaiian as follows: “P” (pī) “A” (ʻā) “PA” (pā) (Schütz, 1994).

The Pūnana Leo Hakalama chart emerged from Hawaiian family-maintained traditions without direct contact of the ʻAha Pūnana Leo with missionary primer charts. Research of those charts and comparison with the Hakalama chart shows considerable differences. Unlike the missionary letter-combination lists, the Hakalama chart is organized horizontally rather than vertically and includes the glottal stop consonant at the end of the first ten lines as well as the differentiation of short and long vowels. The Hakalama chart also includes consonant-less single vowel huahakalama syllables distinct from vowel letters, letters whose Hawaiian names actually begin with the glottal stop (see Fig. 8.7.) These challenging single vowel huahakalama syllables are ordered at the end of the Hakalama chart and contrast with the missionary placement of two vowel-letter combinations earliest in their letter combination list. Note further that those missionary two vowel-letter combinations represent multiple words in Hawaiian pronounced with different combinations of long and short vowels and sometimes the glottal stop. For example “AU” on the missionary chart represents the words: au ʻI,’ a‘u ʻswordfish,’ āu ʻyour,’ ʻau ʻswim,’ andʻāū an exclamation of surprise.

The oral use, as well as the written representation, of the Pūnana Leo Hakalama, differs considerably from the family oral practices of Mrs. Craver and the oral use of the missionary primers. First, recitation of the Hakalama does not involve a preceding recitation of the names of the letters of the Hawaiian alphabet and of Hawaiian numerals as recalled by Mrs. Craver. Then, unlike the missionary method of first spelling and then pronouncing individual words in verticle lists unrelated to the normal flow of reading, the Hakalama methodology involves smooth chanted ‘reading’ of all the huahakalama of the chart from left to right and top to bottom with simultaneous pointing to the individual symbols as they are chanted. The Hakalama methodology thus models the proper procedure for fluent decoding of sentences and paragraphs. Also, unlike the missionary methodology, there is no standard set of words to be taught, but instead an understanding is instilled in teachers regarding what combinations of huahakalama are most easy for initial decoding and which are the most difficult. Those combinations of huahakalama are taught by the teacher with individual words and horizontal lists of words “off the chart.” From there students move to decoding full sentences and paragraphs in simple books.

The Transfer from Reading Hawaiian to Reading Japanese and English

The use of the Hakalama continues from the Pūnana Leo O Hilo into kindergarten at Nāwahī. Then, at first grade, all Nāwahī students are introduced to both oral and written Japanese as part of a ‘heritage language’ program honoring immigrant ancestors who intermarried with Native Hawaiians. Syllabic reading of Hawaiian using Japanese orthographic representations of huahakalama as hiragana and kanji facilitates the transition from reading Hawaiian to reading Japanese.

The other second language studied by all Nāwahī students is English. English is learned as a ‘world language’ to allow communication on a global level. Somewhat similar to some models of teaching English used in Europe (Pufahl, Rhodes, & Christian, 2001), English is introduced at Nāwahī with two fifty-minute classes per week beginning in grade 5. Students continue studying English through the medium of Hawaiian in a single class for the same amount of time through to grade 12.

Beginning literacy is not specifically taught for English at Nāwahī. Students enter grade 5 having already transferred their skills in reading Hawaiian to reading English. The transfer of literacy from Hawaiian to English is facilitated by the use of the same alphabet in the two languages and occurs because of previous student exposure and acquisition of oral and written English through interaction with the larger community. Factors facilitating literacy transfer from Hawaiian to English is the transfer of phonological awareness from Hawaiian to English and other positive effects of bilingualism on English phonological awareness (Cummins, 1981; Canbay, 2011; Cisero & Royer, 1995; Bialystock, 2002; Dickson, McCabe, Clark-Chiarelli, & Wolf, 2004). Similar transfer of indigenous language literacy to literacy in English has been observed with children from other Polynesian language backgrounds in English dominant New Zealand (Tagoilelagi-Leota et al., 2005.

The strong focus on Hawaiian as the medium of education throughout the Nāwahī curriculum provides a strong sense of identity between use of the Hawaiian language and academic success in a college preparatory program. Student skills in English grow over the 8-year period that students study the language, to the point where they are sufficiently prepared in English to enter English medium colleges upon high school graduation, an outcome similar to some European educational systems.

Looking back at the lead class from the Pūnana Leo O Hilo and subsequent classes who have moved through Nāwahī, it is clear that they did not suffer academically from learning to read through the Hakalama or from studying English as a world language. Since its first senior class, Nāwahī has maintained a 100 % high school graduation rate and 80 % college attendance rate. This compares very well with Hawaiʻi public high school graduation and college attendance rates of 82 % and 54 % respectively (Hawaii State Department of Education, 2013).

The Hakalama in the Age of NCLB and ESSA

Passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) by the United States Congress in 2001 and its 2015 reauthorization as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) have created unique challenges for Hawaiian language medium education. There is much irony in the situation as the overall goal of NCLB and ESSA is to improve high school graduation and college attendance rates, especially among those of lower socio-economic backgrounds and from racial and linguistic minorities. The Nāwahī enrollment is approximately 95 % Native Hawaiian with approximately 70 % meeting US federal definitions of low socio-economic status (Wilson & Kamanā, 2011). A very high percentage of the students at Nāwahī also meet the United States federal definition of limited English proficient as almost all use either Hawaiian or Hawaiʻi Creole English at home. In general, the 33 % who speak Hawaiian at home are among the highest performers. The success of these children has inspired more young parents to raise their children as first language speakers of Hawaiian.

Native Hawaiians represent approximately 28 % of the state public school enrollment and are the largest ethnic group in public schools. Native Hawaiian student high school graduation and college attendance has been between 5–20 % and 8–39 % lower, respectively, than that of the next three largest ethnic groups – Caucasians, Japanese, and Filipinos (Kamehameha Kamehameha Schools, 2014). With their high school graduation and college attendance rates above the combined state average for all ethnicities, Nāwahī students are therefore graduating from high school and attending college at rates much higher than are their Native Hawaiian peers.

NCLB and ESSA require academic achievment to be tested through English in order for states to receive federal education funding. Hawaiian is an official language of Hawaiʻi. The only other US jurisdiction with a full education system through a non-English language is Puerto Rico. NCLB allowed Puerto Rico to establish standards through Spanish and test student achievement through Spanish, but Hawaiʻi was not accorded such a provision for its non-English official language. Efforts are being made by the ʻAha Pūnana Leo and other entities to solve this anomoly under the ESSA. In the meantime parents at Nāwahī have been refusing to have their children take state assessments not in the language of instruction (Wilson, 2012).

Challenges also exist for the ʻAha Pūnana Leo at the preschool level and have existed for decades now. Aspects of government and private support for preschools in Hawaiʻi are predicated on accreditation by national preschool education entities. However all of those are English medium entities unfamiliar with teaching through Hawaiian, for example, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC.)

In an effort to demonstrate programatic quality, the ʻAha Pūnana Leo sought the world’s first accreditation based on educational principles articulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The accrediting agency was the World Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium (WINHEC), which in 2014 granted the ʻAha Pūnana Leo a 10-year accreditation. WINHEC’s accreditation team included international experts, among whom were educators fluent in several indigenous languages including Hawaiian. The team singled out the Hakalama reading program for recognition in their final report.

WINHEC accreditation has been helpful with private funding entities, but government entities have yet to accept it. The ʻAha Pūnana Leo is also seeking distinctive state early childhood standards for Hawaiian medium education. The goal is alignment of standards to the distinctive features of literacy acquisition through Hawaiian, as well as the effects of using Hawaiian as the medium of instruction on other early education domains.

With the United States currently focusing on a single path to standards, assessment, and accreditation it is important to note that movements to revitalize indigenous languages and use them in schooling have very limited material and human resources. Those resources are better spent on producing teaching materials, initial teacher education (ITE) programs, and further developing curricula based in the distinctiveness of specific languages than on trying to force endangered indigenous languages into the same box as the huge English language. The ʻAha Pūnana Leo has so far been able to survive while resisting pressure to abandon its distinctiveness including its unique literacy program.

Roots in Tradition Bring Forth Life in Today’s World

Mrs. Mālia Craver’s childhood memories of learning to read by chanted syllables and Niʻihau traditions of public Hawaiian reading by little children have served as a basis for moving the Hawaiian language forward into the twenty-first century.

Fig. 8.9 Pūnana Leo students reading a word syllabically

Recognition of the value of the Hakalama is serving as an entry point for a broader valuing of educational approaches that have deep roots in Hawaiʻi’s distinctive indigenous culture and history.

“ha ka, la ma, na pa, wa ʻa… chant the children as they change society. They carry on a traditional belief that language carries great power and is to be treated carefully and with respect. “I ka ʻōlelo nō ke ola; I ka ʻōlelo nō ka make” says the Hawaiian proverb that has inspired their schooling. ‘In language there is life; In language there is death.’ The Pūnana Leo children are carrying on the life of the Hawaiian language; in turn the language brings life to them, to their families, and to all of Hawaiʻi.